Pourquoi les appareils ne durent souvent pas plus longtemps, de manière intentionnelle ?

Depuis de nombreuses années, certains fabricants raccourcissent délibérément la durée de vie de leurs produits afin de pouvoir en vendre de nouveaux plus souvent.

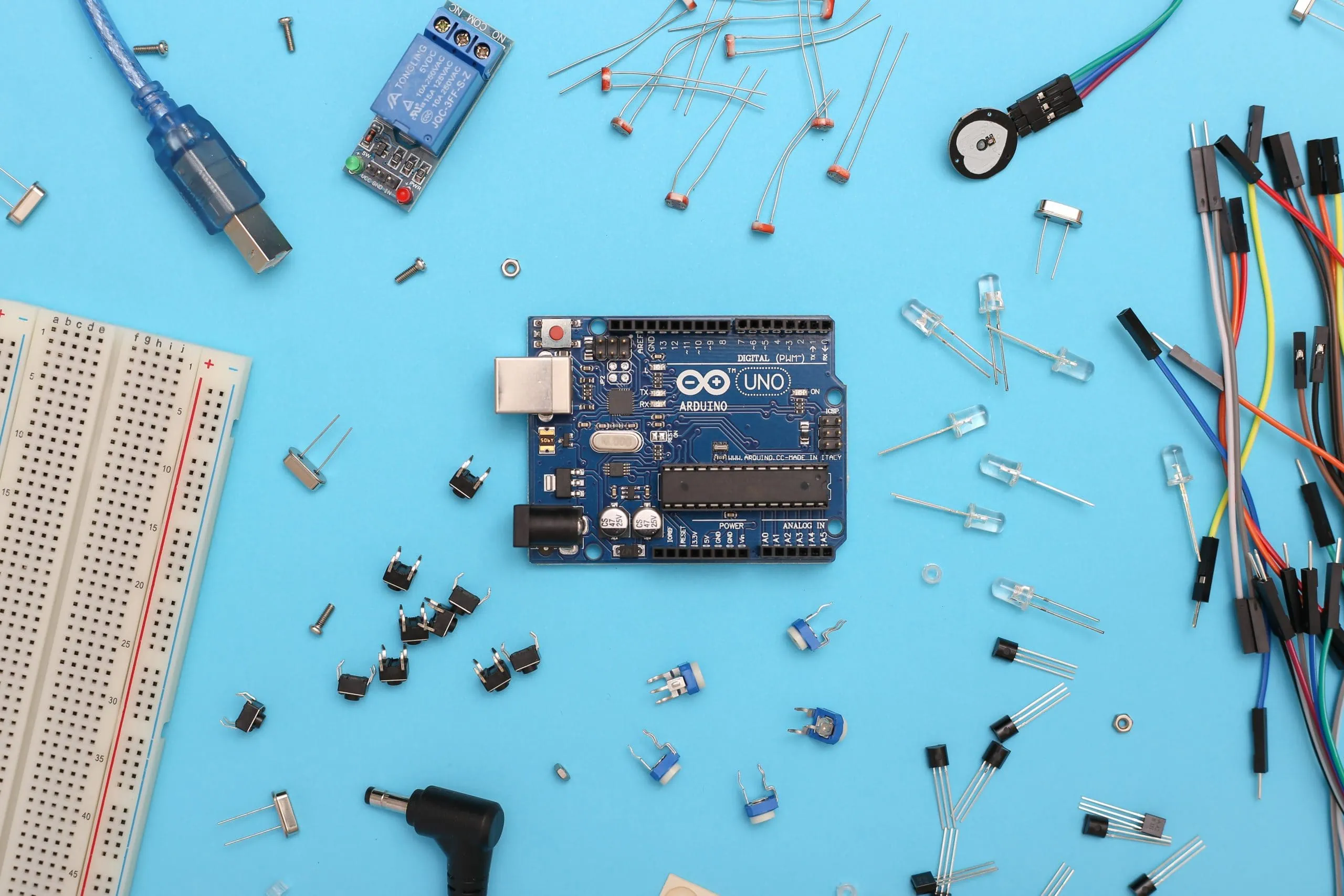

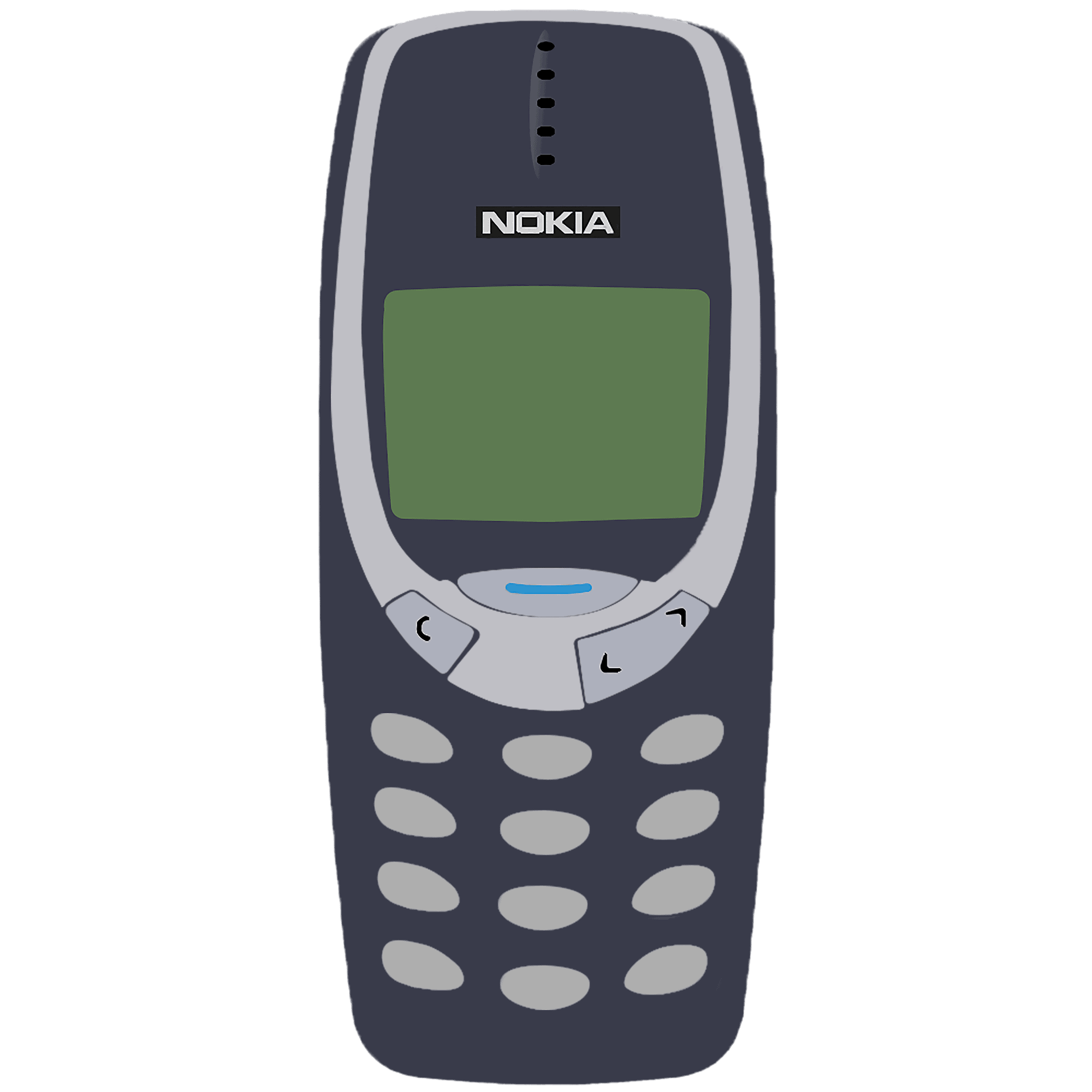

Un très bon exemple est le produit électronique le plus courant – le smartphone. Qui ne se souvient pas des anciens téléphones portables, type l’OS de Nokia, qui ne pouvait certes pas faire grand-chose par rapport aux nouveaux appareils, mais qui était indestructible et qui passe encore aujourd’hui pour presque incassable. Il fonctionne encore de nos jours, même si c’est de manière très limitée. Et la durée de vie de la batterie par rapport aux appareils actuels – est presque infinie.

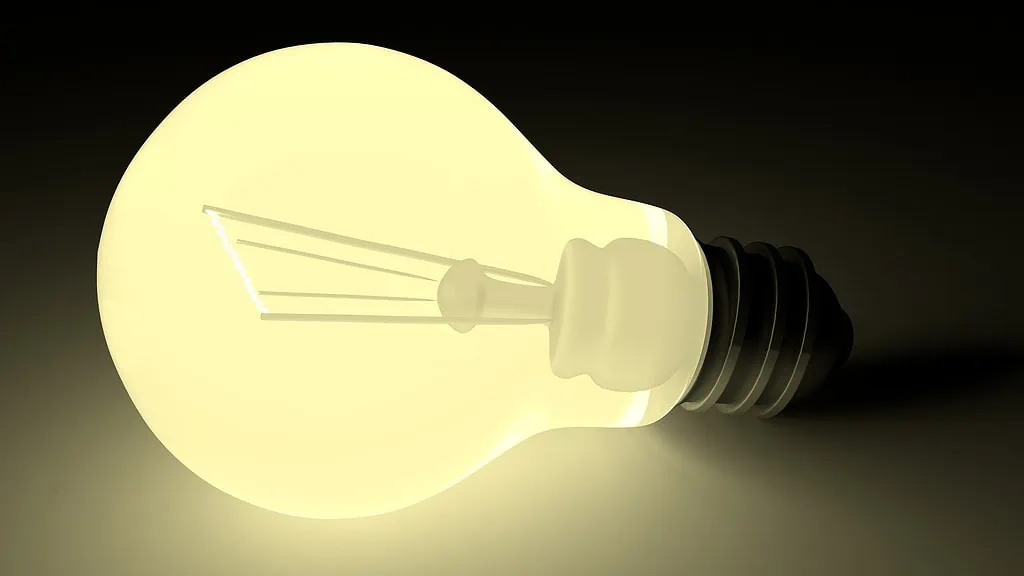

Le cas des ampoules est exemplaire. Les premières ampoules fonctionnaient avec des filaments de carbone et non de tungstène, comme ce fut le cas plus tard. Les filaments de carbone sont environ huit fois plus épais que les filaments métalliques, et donc beaucoup plus durables. Le passage au tungstène a permis d’augmenter la consommation et donc les ventes d’ampoules, et donc … les bénéfices.

C’est ainsi qu’est né, dans les années 1920, le tristement célèbre « cartel Phoebus », au sein duquel les représentants des principaux fabricants mondiaux d’ampoules à incandescence se sont entendus pour réduire artificiellement la durée de vie des ampoules à 1’000 heures. Mais ce n’est qu’un des nombreux secteurs qui ont recours à l’obsolescence programmée.

Elle existe aussi sous différentes formes, de la plus subtile à la moins subtile. De la soi-disant durabilité artificielle, où les pièces fragiles cassent et causent des pannes, aux pièces détachées introuvables, aux coûts de réparation qui sont plus chers que les produits de remplacement, en passant par les mises à niveau esthétiques qui classent les anciennes versions des produits comme dépassées- les fabricants de marchandises connaissent toutes les astuces pour faire payer les clients. Associés à un marketing intensif qui nous fait croire que seul le produit le plus récent est le meilleur, qu’il lave le plus blanc ou qu’il dure le plus longtemps, nous, les consommateurs, tombons dans le panneau.

Les cartouches d’imprimante en sont un autre exemple. Les capteurs sont parfois configurés de manière à indiquer que les cartouches sont vides, alors qu’il y aurait encore suffisamment d’encre. Environ 350 millions de cartouches d’imprimantes sont ainsi jetées chaque année dans les décharges.

Du point de vue de l’environnemental, ces pratiques sont catastrophiques. D’un point de vue macroéconomique, on mentionne malheureusement toujours, que cette pratique crée tout de même des emplois. Mais l’avenir est clairement dans la durabilité. En effet, là aussi, des produits optimisés et plus respectueux de l’environnement permettent de créer de nouveaux emplois, y compris dans le domaine de la réparation et du recyclage, et l’environnement est donc gagnant à long terme.

Que pouvons-nous donc faire en tant que consommateurs ?

Comme le dit l’adage bien connu : le client est roi. Et c’est nous qui déterminons l’offre par notre demande. C’est donc à nous d’adapter notre propre comportement de consommation. Nous ne sommes pas obligés d’avoir le dernier smartphone chaque année, surtout si « l’ « ancien » fonctionne encore normalement. Une utilisation prolongée d’appareils encore en état de marche permet déjà d’économiser beaucoup de déchets. Il n’est par exemple pas nécessaire d’en acheter un nouveau si seul l’écran est un peu cassé – cela peut être réparé. Et même si vous devez remplacer, il ne doit pas nécessairement s’agir d’un produit neuf – il existe aujourd’hui de nombreux fournisseurs qui vendent des appareils d’occasion remis à neuf, mais qui fonctionnent parfaitement. Il est également judicieux de miser sur des modèles dont les différentes pièces peuvent être remplacées séparément si elles tombent en panne. Ainsi, il n’est pas indispensable de changer tout le téléphone portable parce que la batterie est épuisée.

Pour les cartouches d’imprimante, on peut acheter des cartouches rechargeables et économiser encore plus d’encre (niveaux de gris, polices plus fines, etc.) – ou tout simplement en utiliser moins et réfléchir à deux fois avant d’imprimer.

Grâce à Internet et à ses nombreuses évaluations et références ou à la présentation des entreprises, il est aujourd’hui plus facile que jamais de savoir si le nouveau produit ou appareil a une durée de vie courte, si les conditions de travail sont équitables et si la production est locale ou quelles sont les alternatives. Cela vaut aussi bien pour les ampoules que pour les smartphones, les cartouches d’imprimante, les voitures ou même la mode.

Car l’obsolescence programmée n’est pas seulement prévue dans l’électronique. Même les tendances de mode éphémères ne sont rien d’autre qu’une tentative de l’industrie de la mode d’augmenter ses ventes ! Mais comme l’industrie de l’habillement est une des grandes pollueuses au monde, nous ferions bien de changer notre comportement d’achat ici aussi. D’une part, il est raisonnable de ne pas courir après chaque tendance de la mode, mais de miser sur des classiques intemporels. D’autre part, chaque vêtement ne doit pas nécessairement être neuf. Les magasins de seconde main et vintage sont nombreux et proposent un assortiment de premier ordre de grandes pièces uniques de toutes les époques.

Les politiciens et les entreprises commencent également à prendre conscience du changement d’attitude des consommateurs. Dans le cas des ampoules à incandescence, les anciennes ampoules ont été interdites depuis longtemps. Les ampoules LED sont aujourd’hui la norme – elles durent nettement plus longtemps, consomment beaucoup moins, et éclairent de manière tout aussi belle et lumineuse.

Une norme européenne doit obliger les entreprises à prolonger à nouveau la durée d’utilisation des appareils. Notamment en les rendant à nouveau plus faciles à réparer. Mais ce n’est qu’une partie du « deal vert européen » (europa.eu/germany/news), qui vise à faire de l’Europe le premier continent climatiquement neutre d’ici 2050.

C’est important car 45 millions de tonnes de déchets électriques et électroniques sont collectés chaque année dans le monde. Cela comprend aussi de nombreux gadgets dont on n’a pas vraiment besoin. Par exemple, le cadeau de Noël amusant avec une pile fixe que l’on doit ensuite jeter parce que la pile ne peut pas être remplacée !

La réutilisation, la réparation et le recyclage sont le modèle d’avenir pour les appareils et les produits. Ne serait-ce que parce que les ressources nécessaires à la fabrication des appareils (métaux précieux, terres rares, etc.) ne sont pas infinies. Certaines entreprises proposent déjà des primes de reprise. Mais du point de vue de Zero Waste, cela ne va pas encore assez loin. Et c’est pourquoi nous, en tant que consommateurs, devons montrer l’exemple avec notre pouvoir d’achat.

Nous n’achetons que ce dont nous avons effectivement besoin – si possible localement et sans emballage – et nous les utilisons tant que cela est possible. Et quand arrive le moment où cela n’est plus possible, nous devons alors trouver un moyen de réintégrer les matériaux dans le circuit – ou de les utiliser autrement.

Pour d’autres pistes low tech, consultez notre programme Le Zéro Déchet en 10 étapes.